1782

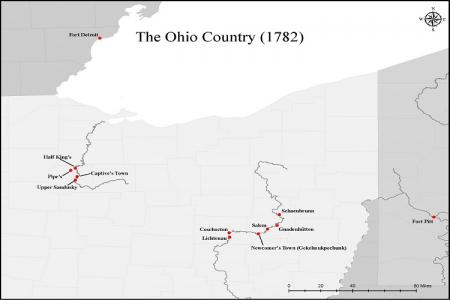

In March 1782, ninety-six Mohican and Delaware Moravians sang hymns as they were murdered by a company of Pennsylvania militiamen at the Moravian mission of Gnadenhütten, Ohio. In the immediate aftermath of the 1780s, an investigation commissioned by President George Washington and the United States Congress could not locate a single person who would admit to having participated in the massacre at Gnadenhütten. None of the perpetrators were ever brought to justice. In the face of such silences, questions of sound—music, agency, and intercultural performance—are particularly urgent. Music possessed the power to unite and divide, to produce understandings and misunderstandings, and to constitute adaptive or destructive strategies for navigating an unprecedented period of cultural shift and physical co-presence between European settlers and Native nations and communities. The singing of the Gnadenhütten community was not coincidental, nor unexpected, and reveals important insights about the beliefs and practices of Native Christians who affiliated with the Moravian church.